This article embarks on an exploration of the Egyptian Gods family tree, a journey through time, culture, and spirituality. Together, we will unravel the secrets of this ancient pantheon, shed light on the dynamics that shaped their mythology, and gain a deeper understanding of the enduring legacy of the Egyptian gods in our world today.

The ancient Egyptians stand out as a civilization deeply enmeshed in the mystical and the divine. Their monumental pyramids, intricate hieroglyphics, and elaborate burial practices have long fascinated archaeologists and historians. Yet, at the heart of this magnificent culture lies an intricate tapestry of gods, goddesses, and mythical beings, which form the backbone of Egyptian spirituality and mythology.

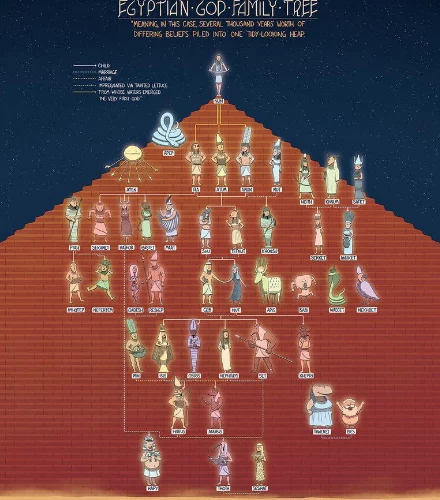

The Egyptian gods, in their multitudes, were believed to control the very fabric of existence, shaping the destinies of both mortals and the cosmos itself. But perhaps one of the most intriguing aspects of this pantheon is the complex interplay between its divine figures – a richly woven tapestry known as the “Egyptian God’s Family Tree.”

The journey through this ancient family tree offers a captivating glimpse into the intricate cosmology and religious beliefs of the Egyptians. It takes us beyond the well-known and omnipresent deities like Ra, Osiris, and Isis, deep into the realms of creation, birth, and the eternal cycle of life and death. To appreciate the grandeur of this pantheon, we must delve into the heart of their beliefs and the divine relationships that shaped their worldview.

Egyptian mythology is not a singular narrative but a collection of stories and concepts that evolved over millennia. It weaves together regional variations, dynastic changes, and the confluence of different religious traditions.

The gods and goddesses, at the heart of this intricate narrative, played multifaceted roles in Egyptian life. They were protectors, judges, healers, and guardians of the afterlife. They represented the forces of nature and embodied the traits of both humans and animals, bridging the gap between the earthly and divine realms.

At the dawn of creation, there existed two distinct groups of gods: the Ogdoad and the Ennead. The Ogdoad, a group of eight primordial deities, symbolized the chaos that preceded the ordered world. The Ennead, on the other hand, represented the harmonious universe, and its members included some of the most prominent gods, such as Osiris, Isis, and Seth.

As we journey deeper into the heart of this family tree, we will uncover the divine offspring of these gods – figures like Horus, Anubis, and Hathor, each with their unique roles and attributes. We will explore the intricate genealogical connections between these deities, as well as the complex relationships, alliances, and rivalries that shaped the course of Egyptian mythology.

What is a family tree?

A family tree, often called a genealogy or pedigree chart, is a visual representation of a person’s ancestry and familial relationships. It traces one’s heritage by illustrating the connections between individuals across multiple generations. Typically, it starts with a single individual, often the person creating the tree, and then branches out to display their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and so on.

Each individual on the family tree is represented by a box or circle, with their name and sometimes key information like birth and death dates. Lines connect these individuals to show parent-child relationships, and the tree expands vertically and horizontally as it includes more relatives.

Family trees serve various purposes, including documenting lineage, understanding one’s roots, and preserving a record of ancestry. They are essential tools for genealogists and historians, helping to uncover family history, uncover hidden stories, and identify relatives.

These diagrams can be as simple as a few generations or as complex as extensive historical records, highlighting the interconnectedness of all family members. Ultimately, a family tree is a meaningful way to visualize and honor the bonds that link individuals across time and generations.

Egyptian Gods and Goddesses Family Tree

The mythology of Ancient Egypt is a labyrinthine tapestry of deities, cosmology, and human existence, with gods and goddesses at its heart. These divine figures shaped every facet of Egyptian life, from birth to the afterlife.

Beyond their individual significance, it is the intricate web of relationships that weaves this pantheon into a rich family tree. In this exploration, we delve deep into the complex genealogical connections between the gods and goddesses, uncovering stories of creation, power, and transcendence.

1. Nun

Nun is not a god in the conventional sense within ancient Egyptian mythology. Instead, Nun is often described as a primordial and abstract deity, representing the concept of the primordial waters or the cosmic ocean from which all life and creation emerged. These waters were believed to be the foundational element of the universe.

In ancient Egyptian cosmology, Nun served as the personification of this boundless, watery abyss and is sometimes referred to as the “Father of the Gods.” While Nun does not possess the distinct personality and attributes commonly associated with other Egyptian gods like Ra, Osiris, or Isis, Nun’s existence is essential to the creation and structure of the Egyptian cosmos.

Nun, an essential figure in ancient Egyptian cosmology and mythology, stands as a primordial deity who played a crucial role in the creation and organization of the universe. Nun symbolizes the vast, boundless waters that predated the world’s existence. In Egyptian cosmogony, Nun’s infinite waters were the cosmic ocean from which life and the physical world emerged.

Depicted as a personification of the watery abyss, Nun is typically portrayed as a bearded man in a prone position, surrounded by the hieroglyph for water. This representation reflects the profound significance of water in Egypt, where the Nile River was the lifeblood of the land, nurturing agriculture and sustaining the population.

Nun’s role in Egyptian mythology extends beyond mere existence as the primordial waters. He served as a foundational element in the creation of the universe, providing the backdrop against which the gods and everything in the cosmos came into being. Thus, Nun’s introduction serves as a gateway to the rich tapestry of ancient Egyptian beliefs and cosmogony, highlighting the cultural importance of water and the divine origins of their world.

2. Apep

Apep, also known as Apophis, is a fascinating and formidable figure in Egyptian mythology. Unlike many other Egyptian deities, Apep was not a god to be revered but a powerful and malevolent force that represented chaos and destruction. Apep embodied the serpent or snake, and it was seen as a monstrous and eternal adversary of the sun god Ra.

Apep’s primary role was to challenge Ra on his daily journey through the underworld and the night sky. This confrontation symbolized the eternal struggle between order and chaos, creation and destruction. Apep was often described as a colossal serpent or dragon, with its enormous body stretching for vast distances. Ra, on his solar boat, would navigate through the underworld each night, and Apep would lie in wait, attempting to devour the sun god and plunge the world into darkness.

To protect Ra and thwart Apep’s malevolent intentions, the gods and goddesses, particularly the god Set, were called upon to defend Ra during this nightly battle. Priests and individuals also played a role in rituals and incantations to aid Ra in his journey and protect the world from Apep’s chaos.

Apep’s significance goes beyond his role in the nightly struggle with Ra. He embodies the concept of isfet, which represents disorder, chaos, and the antithesis of Ma’at, the principle of harmony and balance. In Egyptian cosmology, maintaining Ma’at was essential for a stable and orderly existence, and Apep represented the constant threat to this equilibrium.

3. Aten

Aten, a unique and historically significant deity in Egyptian history, was not a traditional god but rather an abstract and solar concept that gained prominence during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten in the 14th century BCE. Aten, often depicted as a sun disk with rays extending downward, represented the solar disc and the life-giving power of the sun.

The worship of Aten became the central focus of Akhenaten’s religious and political reforms, leading to a brief but dramatic religious revolution known as the Amarna Period. Akhenaten believed that Aten was the supreme, singular, and universal god, and he attempted to shift Egypt’s polytheistic religious practices towards monotheism.

This transformation included moving the capital to a new city, Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna), and closing temples dedicated to other deities.

Aten was characterized as a benevolent and life-giving deity, often depicted with rays of light ending in tiny hands holding ankh symbols (representing life) that extended towards the king and queen. Akhenaten and his family were depicted in a unique and more naturalistic art style that differed from the traditional Egyptian artistic conventions.

The “Great Hymn to the Aten,” a religious text from this period, praises Aten as the creator of life and the natural world. It emphasizes the Pharaoh’s role as the intermediary between Aten and the people.

However, after Akhenaten’s death, Aten’s prominence diminished, and traditional polytheistic religious practices were restored. Temples to other gods were reopened, and Aten was largely forgotten.

The worship of Aten remains a crucial part of Egypt’s religious and cultural history, not only for its uniqueness but also for the insights it provides into the religious and political changes of the Amarna Period and the impact of royal ideology on Egyptian belief systems.

4. Ra

Ra, one of the most significant and enduring deities in ancient Egyptian mythology, was the sun god and often regarded as the creator and supreme ruler of the cosmos. Ra’s name, which is sometimes spelled Re, represents the Egyptian word for the sun, and his worship dates back to the early periods of Egyptian civilization.

Ra was frequently depicted as a man with the head of a falcon, often adorned with a solar disk and a cobra, known as the Uraeus, which represented divine protection. His falcon head symbolized the soaring sun, and the sun disk represented his fiery, life-giving power. Ra was associated with the midday sun, representing its peak strength and life-nurturing capabilities.

One of Ra’s primary roles was to navigate the sky in his solar boat during the day, providing light and warmth to the world. At night, he embarked on a perilous journey through the underworld, battling the serpent god Apep (Apophis) to ensure that the sun would rise again the following day, symbolizing the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

Ra’s significance extended beyond being just a solar deity. He was often fused with other gods, such as Amun, to create powerful combinations like Amun-Ra, demonstrating the synthesis of divine attributes and the adaptability of Egyptian religious beliefs over time.

The city of Heliopolis was particularly dedicated to the worship of Ra, and it was home to a grand temple complex where priests conducted daily rituals to honor the sun god.

The concept of Ma’at, representing order, balance, and harmony, was closely associated with Ra’s rule, highlighting the importance of his role in maintaining cosmic balance. Pharaohs were often seen as the earthly embodiment of Ra, serving as intermediaries between the sun god and the people.

Ra’s enduring legacy in Egyptian culture, along with his connection to the sun and the cycle of life, underscores his prominence and importance in ancient Egyptian mythology, symbolizing the fundamental elements of their cosmological and religious beliefs.

5. Atum

Atum, an ancient Egyptian deity, played a significant role in their cosmology and mythology as the god of creation and the setting sun. Atum represented the concept of the primordial, self-created being and was often depicted as a man with a dual crown, combining elements of both Upper and Lower Egypt. This duality symbolized his status as the god who united the two lands of Egypt.

Atum’s creation myth centered around his self-generation. He was believed to have arisen from the chaotic, watery abyss known as Nun, which predated the world’s existence. Atum was often associated with the setting sun, and his name is linked to the Egyptian word “tem,” meaning “to complete” or “to finish,” signifying the end of the day.

Atum was sometimes associated with the sun god Ra, and in certain religious contexts, they were merged into Atum-Ra, emphasizing the solar aspects of both deities. Atum-Ra was seen as the sun as it dipped below the horizon at sunset, traveling through the underworld at night to rise again at dawn, representing the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

As a creator god, Atum was responsible for giving birth to other deities and all living beings. He was believed to have created the world through the act of self-pleasure, with his hand or breath symbolizing the creative force.

Atum’s worship was particularly prominent in Heliopolis, where he had a dedicated temple. There, he was honored with daily rituals and veneration. His role as a unifying deity who bridged the division between Upper and Lower Egypt was especially crucial during times of political consolidation.

6. Amun

Amun was one of the most influential and versatile deities in ancient Egyptian mythology and served as the god of air and invisibility. His name, sometimes spelled as Amun or Amen, means “hidden” or “the hidden one,” emphasizing his enigmatic nature. Over time, Amun evolved to become one of Egypt’s most powerful and widely worshiped gods, with a complex set of attributes and roles.

Amun was often depicted as a man wearing a tall, feathered crown with two upright plumes, symbolizing his connection to the wind and air. This association with the air reinforced the idea of his hidden or invisible presence, as the air is intangible.

Amun’s significance grew notably during the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom periods, particularly in the latter. He merged with the sun god Ra to become Amun-Ra, symbolizing the combination of solar and creative attributes. This fusion emphasized Amun’s role as the ultimate creator and ruler of the cosmos, often depicted as a ram-headed figure or as a man with a sun disk.

The city of Thebes, modern-day Luxor, was a focal point of Amun’s worship. The temple complex of Karnak, dedicated to Amun-Ra, became one of the largest religious structures in the ancient world. The power of the Amun clergy grew immensely, and the god himself was hailed as the “King of the Gods.”

Amun’s role extended beyond creation; he was associated with fertility, protection, and pharaohs’ divine authority. The pharaohs considered Amun to be their personal patron and an intermediary between themselves and the divine realm.

Amun’s adaptability and widespread veneration reflected the dynamic nature of Egyptian religious beliefs and the god’s capacity to incorporate different attributes and roles. His cult continued to influence Egyptian religion even after the decline of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Amun’s legacy underscores the flexibility and enduring influence of this ancient deity, who symbolized the hidden forces that shaped the cosmos and human destiny.

7. Mut

Mut was associated with motherhood, protection, and the primal energy of the cosmos. Her name, Mut, means “mother,” and she was often represented as a woman wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, signifying her status as a powerful and protective deity.

Mut’s primary role was that of a mother goddess and protector. She was often depicted with a lioness head or as a lioness, emphasizing her fierce and nurturing qualities. This connection to lions symbolized her role as a guardian and protector of pharaohs, who were often considered her earthly children. The great warrior goddess Sekhmet was sometimes identified as an aspect of Mut, underscoring her protective and sometimes destructive attributes.

One of the most famous centers of Mut’s worship was the temple of Karnak in Thebes, where she was honored as the consort of Amun-Ra. Together with Amun-Ra and their son Khonsu, they formed the Theban Triad, a powerful divine family that played a crucial role in the religious and political landscape of ancient Thebes.

Mut’s role in the Egyptian pantheon was both maternal and cosmic. She was believed to have given birth to the cosmos, and her nurturing qualities extended to the entire world. Her worship, particularly in the New Kingdom, emphasized the importance of motherhood, fertility, and the divine protection of pharaohs and their subjects.

Over time, Mut’s role continued to evolve, and she was often incorporated into the attributes of other goddesses, such as Hathor and Isis. Her influence endured, and she remained an essential and revered figure in Egyptian mythology, reflecting the enduring significance of motherhood, protection, and cosmic order in the ancient Egyptian belief system.

8. Hathor

Hathor is a significant and multifaceted goddess in ancient Egyptian mythology, held a central role in various aspects of life, including love, motherhood, music, and the afterlife. Her name, often written as “Hat-Her,” means “House of Horus,” linking her to the sky god Horus.

Hathor was typically depicted as a woman with cow’s ears, or as a woman with a crown consisting of a sun disk, cow horns, and cobras. The cow was a sacred symbol in Egyptian culture, representing fertility and abundance, and Hathor was seen as a nurturing and protective deity.

Hathor was closely associated with music, dance, and joy. She was often invoked during celebrations and festivals, and her role as a goddess of love and beauty made her a patron of music, dance, and romance. In this capacity, she was believed to inspire creativity and harmony in both divine and mortal realms.

As the goddess of motherhood and fertility, Hathor played a vital role in women’s lives, particularly during childbirth. Women sought her protection and blessings during pregnancy and labor, and she was also considered the divine wet nurse who nourished the infant pharaohs.

Hathor’s complex nature extended to her role in the afterlife. She was believed to assist the deceased on their journey to the next world and provide them with sustenance and protection. Her nurturing attributes were essential for ensuring a smooth transition to the afterlife.

Hathor’s worship was widespread throughout Egypt, with notable centers in Dendera and Thebes. The Temple of Hathor at Dendera is one of the best-preserved ancient Egyptian temples, richly decorated with scenes depicting the goddess’s many aspects.

9. Sekhmet

Sekhmet, a fierce and powerful goddess in ancient Egyptian mythology, embodied the attributes of war, destruction, and healing. Her name, derived from the Egyptian word “sekhem,” means “power” or “might,” reflecting her formidable nature.

Sekhmet was often depicted as a woman with the head of a lioness or as a full lioness, emphasizing her connection to ferocity and bravery in battle. She was frequently associated with the sun, fire, and the desert, symbolizing both destructive and life-giving aspects.

Her primary role in Egyptian mythology was as the warrior goddess and protector of the pharaoh. Sekhmet was believed to be the fiery and wrathful aspect of the goddess Hathor, and she was called upon to defend against Egypt’s enemies and to maintain cosmic balance. Her fiery breath and gaze were thought to have the power to vanquish foes and restore order.

Despite her fierce attributes, Sekhmet had a multifaceted nature. She was also revered as a goddess of healing and medicine. In this benevolent aspect, she was known as “Lady of Life” and was believed to have the power to cure illnesses and plagues. Temples dedicated to her often included infirmaries where people sought her aid in times of sickness.

The city of Memphis was one of the primary centers of Sekhmet’s worship, and the temple there, known as the “House of Life,” was dedicated to both Sekhmet and her benevolent counterpart, Bastet, who was a lioness goddess of home, fertility, and protection.

10. Bastet

Bastet was an important and complex deity in ancient Egyptian mythology and was primarily revered as a goddess of home, fertility, women, and domesticity. Her name, often spelled as “Bast” or “Bastet,” means “She of the Ointment Jar,” reflecting her nurturing and protective aspects.

Bastet was typically depicted as a lioness or as a woman with a lioness head, representing her dual nature as a gentle, nurturing goddess and a fierce protector. In her lioness form, she symbolized strength and ferocity, while in her more human-like form, she represented the qualities of motherhood and home.

One of her primary roles was to safeguard the home, ensuring harmony, fertility, and domestic well-being. She was believed to be the guardian of families and households, keeping them safe from evil influences and negative forces.

Bastet was also associated with music and dance, and she was considered a patron of the arts. Her festivals included lively celebrations with music, dance, and offerings to honor her protective qualities.

Over time, Bastet’s image and role evolved. In the earlier periods of Egyptian history, she was more closely aligned with the lioness goddess Sekhmet, particularly as a goddess of war and destruction. However, in later periods, she underwent a transformation into a gentler, domestic goddess. She became known as the “Lady of the East,” symbolizing the gentle rays of the rising sun, which were associated with new beginnings and renewal.

The city of Bubastis, located in the Nile Delta, was the primary center of Bastet’s worship. The city’s grand temple complex, known as the “House of Bastet,” was renowned for its vibrant festivals and religious significance.

11. Maat (Ma’at)

Ma’at, an essential and profound concept in ancient Egyptian culture, represents the principles of balance, harmony, and truth. While Maat is not a deity in the traditional sense, it embodies a fundamental concept that influenced Egyptian religion, society, and governance.

The word “Ma’at” itself translates to “truth” or “order,” and it is symbolized by an ostrich feather, often worn on the headdresses of deities and pharaohs. Ma’at is the counterbalance to “Isfet,” representing chaos and disorder. It signifies the universal order and ethical values that ancient Egyptians believed governed the cosmos.

Ma’at had a multifaceted role in Egyptian belief systems. It was both a cosmic force and a moral imperative. In a cosmic sense, Ma’at maintained the order and regularity of the universe, ensuring the predictability of natural phenomena, such as the annual flooding of the Nile.

It was also linked to the afterlife, where the deceased’s heart was weighed against Ma’at’s feather in the judgment of the dead. If the heart was found to be lighter than the feather, the individual was deemed virtuous and allowed to enter the afterlife.

In terms of morality and ethics, Ma’at provided a framework for individual behavior and social interactions. Ancient Egyptian laws and ethical guidelines were rooted in the principles of Ma’at, emphasizing honesty, justice, kindness, and integrity. Pharaohs were considered the upholders of Ma’at on Earth, responsible for maintaining cosmic order and justice in their society.

The goddess Ma’at, who personified this concept, was often depicted as a woman with an ostrich feather on her head. She served as a symbol of the values and principles that were integral to Egyptian life.

12. Shu

Shu, a deity in ancient Egyptian mythology, played a crucial role in the creation and sustenance of the cosmos. He was the god of air and wind, symbolizing the life-giving breath that separated the sky from the earth. Shu’s name means “emptiness” or “he who rises up,” reflecting his role in maintaining the fundamental separation between the heavens and the earth.

Shu was typically depicted as a man standing on the back of the sky goddess Nut, holding her up and creating the space between her and her brother and husband, the earth god Geb. This separation of Nut and Geb allowed for the existence of the physical world and served as a representation of cosmic order.

Shu’s role as the god of air and wind was vital in Egyptian cosmology. He provided the atmosphere, which was essential for life, and his presence ensured the breathable air that sustained all living beings. Additionally, he was linked to sunlight and the warmth of the sun, further emphasizing his life-giving attributes.

Shu was also associated with the falcon, a bird that was often linked to the sky and the sun. This connection reinforced his role in the celestial realm.

Despite not being one of the most widely worshiped deities, Shu’s significance lay in his contribution to the creation and sustenance of the universe.

He upheld the cosmic order, ensuring that the boundaries between the sky and the earth remained intact, allowing for the existence of life and the preservation of Ma’at, the principle of balance and harmony, in ancient Egyptian belief systems.

13. Tefnut

Tefnut, an ancient Egyptian goddess, played a pivotal role in the creation and balance of the universe. She represented moisture, specifically the concept of both dew and rain, and was regarded as a fundamental element in the cosmic order.

Tefnut was typically depicted as a lioness-headed or lioness-bodied woman, symbolizing her connection to the fierce and life-giving aspects of moisture. In some depictions, she wore the solar disk and the Uraeus, the cobra, on her head, underlining her significance as a protective deity.

In Egyptian cosmology, Tefnut was considered one of the first deities in existence, born from the tears of Atum, the primordial god. She was often paired with her brother and consort, Shu, the god of air. Together, they represented the elements of air and moisture, which were essential for life and the creation of the physical world.

Tefnut’s presence was instrumental in maintaining cosmic balance and order. Her moisture was crucial for fertility and agriculture, as it played a significant role in the annual flooding of the Nile River, which enriched the soil and allowed for bountiful harvests.

Tefnut’s mythology also extended to her role in the creation of the cosmos. She and Shu were responsible for creating the first generation of deities, including Nut, the sky goddess, and Geb, the earth god, by physically separating them from their initial entwined state. This separation formed the framework of the universe, allowing for the existence of life and a structured world.

14. Khonsu

Khonsu, a god in ancient Egyptian mythology, was primarily associated with the moon, time, and healing. He was considered a member of the Theban Triad, which included his parents, Amun and Mut. Khonsu was particularly revered in Thebes, where he was considered a local deity with a significant following.

Khonsu was typically depicted as a young man with a sidelock of hair, often holding the ankh (a symbol of life) and the djed pillar (symbolizing stability). The sidelock represented youth, and it was a common motif in depictions of Khonsu. He was sometimes also depicted as a child or a baboon.

One of Khonsu’s most notable roles was his association with time and the lunar calendar. As the moon god, he was believed to have the power to influence the passage of time and the phases of the moon. He played a crucial role in religious festivals and lunar observations that helped determine the timing of various rituals and events.

Khonsu was also considered a healing deity, particularly in relation to mental and psychological disorders. He was invoked for help in curing illnesses of the mind, such as depression and anxiety. His healing attributes were closely linked to his lunar associations, as the phases of the moon were believed to impact mental well-being.

The city of Karnak, near Thebes, was a significant center of Khonsu’s worship, and it housed a temple dedicated to him. The annual Festival of Khonsu was a major event in Thebes, drawing pilgrims and devotees from various parts of Egypt.

15. Ptah

Ptah held a central role in the creation of the universe and was associated with craftsmanship, architecture, and the arts. He was regarded as a creator god, representing the power of thought and the spoken word in bringing the world into existence.

Ptah was typically depicted as a mummiform figure, often holding an ankh (a symbol of life) and a scepter. He wore a skullcap and a long beard, which symbolized his enduring creative power. His appearance was notably distinct from other Egyptian gods.

One of Ptah’s most significant attributes was his association with Memphis, where he was the principal god. The city was home to the grand temple of Ptah, known as the “House of Ptah,” which was one of the most important religious centers in ancient Egypt. This temple served as the epicenter of Ptah’s worship and attracted pilgrims and devotees from across the region.

Ptah’s most distinctive role was his connection to the concept of creation. In ancient Egyptian cosmology, it was Ptah who thought the world into existence, and his divine words became reality. He was regarded as the ultimate craftsman and architect, often referred to as the “Great Artificer” or the “Noble Djed.” His creative powers extended not only to the physical world but also to the arts, literature, and the written word.

As a deity of craftsmanship and the arts, Ptah was the patron of skilled artisans and craftsmen. His divine guidance was sought by those who worked in fields like sculpture, jewelry making, and construction. His importance in the realm of artistic and architectural creation underlined the significance of his role in shaping ancient Egyptian culture.

16. Qadesh

Qadesh, also spelled as Qedesh, was a goddess in ancient Egyptian and Canaanite mythology. Her name means “the holy” or “the sacred,” underlining her role as a divine and revered figure. While she primarily originated in the Canaanite pantheon, Qadesh was also incorporated into certain aspects of Egyptian religion.

Qadesh was often depicted as a young, beautiful woman, typically standing nude or semi-nude, emphasizing her sexuality and desirability. Her imagery was characterized by her youthful appearance and attributes associated with love, sexuality, and fertility.

In Egyptian beliefs, Qadesh was sometimes associated with the goddess Hathor, particularly in her aspect as Hathor of Qadesh, highlighting the connection between love, desire, and female divinity.

Qadesh’s cult had its center in the city of Qadesh in modern-day Syria, which played a significant role in the trade routes connecting Egypt and the ancient Near East. As a result, her worship and influence extended beyond the borders of Egypt and was embraced by different cultures in the region.

17. Reshep

Reshep was a deity in ancient Egyptian and Canaanite mythology, represented the god of lightning, thunder, and war. His name, which means “burning,” reflects his association with fiery and destructive forces. Reshep was typically depicted as a warrior god, often shown holding a weapon or a mace, emphasizing his martial attributes.

In Egyptian beliefs, Reshep was sometimes associated with other warlike deities, such as Montu and Sekhmet, highlighting his role in the pantheon as a god of battle and protection. His association with thunder and lightning underscored his capacity to bring destruction and chaos in warfare.

Reshep’s cult was likely introduced to Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, a time marked by increased foreign influence and the blending of various religious traditions. He was particularly venerated in the eastern Delta region, where his cult center, known as the “House of Reshep,” was located.

In Canaanite mythology, Reshep was also linked to fertility and protection, where he was often invoked to safeguard against illness and evil forces.

Reshep’s significance in both Egyptian and Canaanite beliefs illustrates the syncretic nature of ancient Egyptian religion and its openness to incorporating deities from neighboring cultures.

As a god of war and destructive forces, Reshep played a role in safeguarding the Egyptian people from external threats, reinforcing the idea that deities were often invoked for their protective and martial attributes in times of conflict and uncertainty.

18. Taweret

Taweret was a figure associated with childbirth, fertility, and protection. Her unique and distinctive appearance reflected her composite nature, combining features of a hippopotamus, a crocodile, and a lioness. Taweret’s name, which can be translated as “The Great One,” emphasized her formidable and protective qualities.

Taweret was often depicted as a goddess with the body of a pregnant hippopotamus, the limbs and paws of a lioness, and the tail of a crocodile. This composite form represented her nurturing and protective attributes. The hippopotamus was a symbol of fertility and motherhood in Egyptian culture, while the lioness and crocodile symbolized strength and ferocity.

Taweret played a crucial role in protecting women during pregnancy and childbirth. Her image was often carved into furniture, such as headrests, or worn as amulets to provide a sense of security and safeguard the expectant mother and her child from malevolent forces and complications during labor.

Taweret was also associated with household protection, guarding homes against evil spirits and chaos. She was believed to help maintain order and harmony in the household, ensuring the well-being of its inhabitants.

Her distinctive and composite appearance was a visual representation of her diverse attributes, offering comfort and safeguarding those in need, especially expectant mothers and their children.

19. Bes

Bes was a household deity associated with protection, fertility, and music. His appearance, which set him apart from other Egyptian deities, was characterized by his dwarf-like figure, often depicted with a lion’s mane and a protruding tongue. He was a jovial and sometimes comical figure who was believed to ward off evil spirits and bring happiness to the home.

Bes was particularly revered as a guardian of women and children. He was thought to protect households from malevolent forces, ensuring the well-being of families. His image was commonly used on amulets, jewelry, and pottery, emphasizing his role in safeguarding against negative influences.

Bes also played a significant role in fertility and childbirth. He was often invoked during labor and was associated with musical and dance performances intended to ease the pain and anxiety of childbirth. His lively and humorous representation was believed to have a comforting and calming effect.

Bes was not confined to the domestic sphere. His playful and energetic nature made him a popular figure in celebrations and festivals, where he was believed to bring joy and merriment to the participants.

While Bes was not a major deity in the official state religion, his enduring popularity and presence in everyday life made him a beloved figure among the ancient Egyptians. His playful character, unique appearance, and protective qualities underlined the importance of joy, protection, and well-being in Egyptian households and celebrations.

20. Imhotep

Imhotep is best known as a historical person rather than a god. He was a polymath who served as a chancellor to Pharaoh Djoser during the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Imhotep’s name means “He who comes in peace,” and he is primarily recognized as a scholar, architect, and physician rather than a deity.

Imhotep’s remarkable achievements and reputation led to his deification in later periods of ancient Egyptian history, particularly during the Late Period and the Ptolemaic Period. He was revered as a god of wisdom, medicine, and science, and he became associated with Thoth, the god of knowledge.

Imhotep’s most famous achievement was the design and construction of the Step Pyramid in Saqqara, which was an architectural marvel and one of the earliest known pyramids in Egypt. His contributions to medicine and healing practices also elevated him to a divine status associated with curing illnesses.

In the Ptolemaic period, a cult centered around Imhotep developed, and temples and shrines were dedicated to him. These centers often included medical facilities, emphasizing his role as a god of healing.

Imhotep’s deification showcased the enduring respect and admiration he earned for his contributions to architecture, medicine, and knowledge. His legacy as a scholar and the world’s first recorded multi-genius is a testament to the intellectual and creative achievements of ancient Egypt, and his deification serves as a reflection of the profound impact of his work in the subsequent eras of Egyptian history.

21. Nefertem

Nefertem was associated with beauty, fragrance, and healing. His name, which means “The Beautiful One,” reflects his primary attribute of beauty. Nefertem was often depicted as a young man holding a lotus flower, emphasizing his connection to both beauty and rebirth.

In Egyptian mythology, Nefertem was believed to have emerged from the primordial lotus flower that blossomed from the watery chaos at the dawn of creation. This association with the lotus, a symbol of rebirth and purity, underlined Nefertem’s role as a deity of renewal and rejuvenation.

Nefertem was often considered the son of Ptah, the creator god, and Sekhmet, the lioness goddess of war and healing. In this familial context, Nefertem was regarded as a soothing and pacifying influence, balancing Sekhmet’s more aggressive attributes.

Nefertem’s symbolism extended to healing and medicinal properties. The lotus flower, which he often held, was believed to have healing qualities, and Nefertem was invoked in rituals related to health and well-being. He was also associated with perfumes and cosmetics, highlighting his role in enhancing physical beauty and personal care.

22. Geb

Geb was the god of the earth and the physical world. His name, which can be translated as “earth” or “soil,” underlines his essential role in the Egyptian cosmology as the embodiment of the terrestrial realm.

Geb was often depicted as a man lying on the ground, with his body representing the earth’s surface. He was often shown colored green to symbolize the fertile soil. His skin was decorated with images of plants, emphasizing his connection to the earth’s vegetation and growth.

As the god of the earth, Geb was believed to be the father of all living beings, including deities and humans. He was closely associated with the sky goddess Nut, his sister and wife, who was believed to arch over him, with her body forming the sky. Their union was thought to be the source of all life and creation.

Geb’s significance extended to the realms of agriculture and fertility. Ancient Egyptians believed that the cycles of sowing and harvest were directly linked to his well-being and mood, and thus, they offered prayers and rituals to ensure his favor and the prosperity of their crops.

While Geb played a foundational role in the Egyptian belief system, his worship was often intertwined with that of other deities, such as Osiris and Ra. He served as a reminder of the earth’s life-giving qualities and the interconnectedness of the natural world.

23. Nut

Nut, a central goddess in ancient Egyptian mythology, personified the sky and heavenly vault. Her name, pronounced as “Newt” or “Noot,” means “sky” or “firmament,” highlighting her role in the cosmos. Nut was often depicted as a woman arched over the earth, with her body forming the sky.

One of Nut’s most iconic representations was as a woman covered in stars, with her limbs stretched over the world, touching the horizon. Her body symbolized the celestial expanse, and her starry form underlined her association with the night sky.

In Egyptian cosmology, Nut was believed to be the mother of the sun god Ra and the moon god Thoth. She was also the sister and wife of Geb, the earth god. Their union was thought to be the source of all creation, as Nut arched over Geb, creating the space between the earth and the sky.

Nut played a crucial role in the ancient Egyptian concept of the afterlife. She was believed to swallow the sun at sunset and give birth to it at sunrise, signifying the daily cycle of death and rebirth. This idea of Nut as a celestial mother was integral to the Egyptian beliefs about death and resurrection.

Nut’s presence in Egyptian culture emphasized the interconnectedness of the earth and the heavens. Her representation as the sky encompassing the earth reinforced the importance of cosmic balance and harmony in the lives of the ancient Egyptians.

24. Babi

Babi is a figure associated with aggression and primordial chaos. His name, pronounced as “Bab-ee,” is often translated as “Bull of the Baboons,” emphasizing his fierce and animalistic characteristics.

Babi was typically depicted as a baboon or as a man with a baboon’s head, symbolizing his connection to the aggressive and unpredictable nature of primordial chaos. He was often portrayed in scenes of the underworld, where he was believed to dwell, and where he played a role in the judgment of the dead.

In Egyptian mythology, Babi was considered a deity of violence and disorder. His presence was associated with chaos and the forces of nature that could not be controlled. As such, he was not a god who received widespread worship or devotion.

Babi’s association with the judgment of the dead was rooted in his role as a symbol of the chaos that individuals had to overcome to achieve order and harmony in the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians believed that passing the tests and challenges represented by figures like Babi was essential for a successful journey to the afterlife.

Despite not being a major deity, Babi served as a reminder of the forces of chaos that existed alongside the ordered world of the living. His role in the underworld highlighted the Egyptians’ belief in the need to overcome chaos to attain a state of harmony and eternal life in the afterlife.

25. Min

Min was associated with fertility, agriculture, and the procreative forces of nature. His name, pronounced as “Meen,” is often translated as “The Bull of His Mother,” underscoring his primary attribute of virility and the regeneration of life.

Min was typically depicted as a god with an erect phallus, symbolizing his role in fertility and procreation. He was often shown wearing a white crown with two tall plumes and sometimes carrying a flail, signifying his dominion over the natural world.

Min was venerated as a deity who oversaw the growth of crops, particularly in the Nile Delta region where he was highly revered. He was believed to ensure bountiful harvests and the fecundity of the land. His association with vegetation, particularly lettuce and other green plants, was rooted in the idea of agricultural abundance.

Min’s influence extended beyond agriculture to the realm of human procreation. He was considered a protector of marriages and a guardian of sexual potency, and his image was often invoked in fertility rituals and ceremonies.

Min’s cult was particularly significant in the city of Akhmim, where his worship thrived. His festivals included joyful celebrations and rituals, often accompanied by music and dance, to invoke his blessings for the well-being of the land and its people.

26. Isis

Isis was a powerful goddess and a central figure in the Egyptian pantheon. She was the sister and wife of Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and the mother of Horus, the god of kingship. Her name, pronounced as “Aye-sis,” translates to “Throne” or “Queen of the Throne,” emphasizing her royal and maternal attributes.

Isis played a multifaceted role in Egyptian beliefs. She was known as the great mother goddess, symbolizing fertility, motherhood, and protection. As the wife of Osiris, she was deeply connected to resurrection and the afterlife, as she played a pivotal role in Osiris’s revival and his role as a judge of the dead.

Isis was revered as a goddess of magic and healing. She was believed to possess powerful knowledge of spells and incantations, which she used to heal the sick and to assist those in need. Her magical nature made her a beloved and accessible deity for the ancient Egyptians, as they sought her guidance and aid in various aspects of life.

Her mythology includes the story of Osiris’s murder by his brother Set and his subsequent resurrection by Isis, highlighting themes of death and rebirth. This narrative was central to Egyptian beliefs about the cycle of life and death and the promise of an afterlife.

The worship of Isis extended beyond Egypt, and her cult had a significant presence in the Mediterranean world, including Greece and Rome. Her enduring legacy underlines her importance in ancient Egyptian culture as a symbol of divine femininity, maternal care, and the mysteries of life and death.

27. Osiris

Osiris, one of the most revered deities in ancient Egyptian mythology, was the god of the afterlife, rebirth, and the Nile’s annual flooding. His name, pronounced as “Oh-sigh-ris,” signifies “Seat of the Eye” or “He Who Rests,” reflecting his central role in the Egyptian belief system.

Osiris was typically depicted as a mummified figure wearing the Atef crown, a white crown with ostrich feathers, which symbolized his dominion over Upper Egypt. His green or black skin color was a representation of rebirth and fertility. His regal bearing highlighted his significance as a god of kingship.

One of the most enduring aspects of Osiris’s mythology is the story of his murder by his brother Set, the god of chaos and disorder. Following his death, Osiris was resurrected by his sister and wife, Isis, and became the ruler of the afterlife. This narrative embodied the concept of death and rebirth and played a fundamental role in Egyptian beliefs about the eternal cycle of life.

Osiris was considered a benevolent and just god who presided over the judgment of the dead. In the afterlife, he would weigh the hearts of the deceased against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice, determining their fate. Those found worthy would proceed to eternal life, while others would face punishment.

The annual flooding of the Nile River, which brought fertility to the land, was believed to be influenced by Osiris. His connection to the agricultural cycle reinforced his importance in Egyptian culture, as it ensured the success of their crops and the well-being of their society.

28. Nephthys

Nephthys played a pivotal role in Egyptian mythology, often alongside her more well-known sister, Isis. Her name, pronounced as “Nep-this” or “Neb-ti,” means “Mistress of the House,” reflecting her association with domestic and familial matters.

Nephthys was typically depicted as a woman with a headdress resembling a house or a basket, highlighting her role as a protector of the home and guardian of the deceased. In Egyptian cosmology, she was believed to be the sister of Isis, the wife of Osiris, and the mother of Anubis, the god of mummification.

Nephthys played a dual role in Egyptian mythology. On one hand, she was considered a protective deity, particularly in the realms of childbirth and the care of the deceased. She was often invoked as a guardian during labor and was believed to provide support and protection to expectant mothers.

In the context of the dead, Nephthys was seen as a comforting and guiding presence for the souls of the deceased. She was associated with the embalming process and the wrapping of mummies, emphasizing her role in ensuring a smooth transition to the afterlife.

Despite her less prominent status compared to deities like Isis or Osiris, Nephthys was a vital figure in Egyptian religious practices, contributing to the safety of homes and the sanctity of the deceased. Her enduring significance underscored the importance of domestic life, family, and the care of the deceased in ancient Egyptian culture.

29. Set (Seth)

Set, also spelled as Seth, was a complex and multifaceted deity in ancient Egyptian mythology. His name, pronounced as “Set,” is often translated as “The Instigator” or “The Red One,” signifying his role as a god associated with chaos, deserts, and storms.

Set was typically depicted as a creature with an animal-like head, which has been variously described as resembling an aardvark or a mythical composite beast. He had long, erect ears and a curved snout, representing the enigmatic and unsettling nature of this god.

Set’s mythology was marked by his role in the murder of his brother Osiris, the god of the afterlife, whom he dismembered and scattered. This act of fratricide established Set as a deity of chaos, violence, and disruption. Conversely, it also positioned him as a symbol of necessary conflict, as his actions led to the development of the Osirian cycle and the concepts of death and resurrection.

Set’s attributes were often seen as negative, particularly in contrast to the benevolent and just gods like Osiris and Horus. He was frequently associated with the forces of evil and disorder, and his image was invoked to repel malevolent influences.

Despite his unsettling reputation, Set was not universally reviled. In some aspects, he was seen as a protector against harmful creatures, such as snakes and scorpions. He was also considered a god of foreign lands and the distant deserts, areas that were sometimes perceived as sources of mystery and danger.

30. Horus

Horus was worshipped as the god of kingship, the sky, and war. He was one of the most widely revered and enduring gods in the Egyptian pantheon. His name, pronounced as “Hor-us,” means “The Distant One” or “He Who is Above.”

Horus was typically depicted as a falcon-headed god or as a man with a falcon’s head, representing his association with the sky and the falcon as a symbol of kingship. The Eye of Horus, also known as the Wedjat or the Eye of Ra, was a powerful symbol that represented protection and good health. It was often invoked in ancient Egyptian culture to ward off evil and promote healing.

One of the most famous aspects of Horus’s mythology is the conflict with Set, the god of chaos, which resulted in the loss of Horus’s eye and its subsequent restoration. This narrative symbolized the eternal struggle between order and chaos and the rightful claim to the throne of Egypt. Horus was considered the protector of the reigning pharaoh and a symbol of the divine legitimacy of the Egyptian kings.

Horus also played a role in the solar cycle, being associated with the daily journey of the sun across the sky. He was linked to the rising and setting of the sun and was believed to be a vital force in maintaining cosmic order and the cycle of life.

31. Anubis

Anubis was the god of mummification, the afterlife, and the guardian of tombs. His name, pronounced as “An-yoo-bis,” is often translated as “Royal Child” or “He Who Counts.”

Anubis was typically depicted with the head of a jackal, a scavenger animal often seen near burial sites, highlighting his role in guiding the deceased to the afterlife. His black color symbolized rebirth and the fertile soil along the Nile.

Anubis played a crucial part in the process of preparing the deceased for the afterlife. He was responsible for the ritual of mummification and the careful preservation of the body to ensure a successful journey to the realm of the dead. His guidance was considered vital in leading souls through the perilous journey to the judgment of Osiris, the god of the afterlife.

In Egyptian beliefs, Anubis was the protector of graves and cemeteries, and his presence was invoked to safeguard against grave robbers and malevolent spirits. He was also associated with the weighing of the heart ceremony, in which the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice. This judgment determined the fate of the soul in the afterlife.

Anubis was a benevolent and compassionate god, guiding the deceased with care and ensuring their safety during their passage to the afterlife. His enduring significance in ancient Egyptian culture underscored the profound importance of death and the afterlife, as well as the meticulous rituals associated with the preservation of the deceased and their journey to the realm of the gods.

32. Apis

Apis was the sacred bull and a symbol of fertility and strength. His name, pronounced as “Ahp-is,” means “Bull,” signifying his primary association with bovine qualities.

Apis was often depicted as a black bull with specific markings, including a white diamond-shaped mark on his forehead and the image of an eagle on his back. These distinctive physical characteristics made him easily recognizable and underlined his sacred status.

The cult of Apis was centered in the city of Memphis, where he was venerated as a god associated with fertility and vitality. His presence was believed to bring prosperity to the land, and he was linked to the Nile’s life-giving properties.

Apis was considered an intermediary between the divine and human realms. His cult played a significant role in ancient Egyptian religious ceremonies and rituals, particularly during celebrations of fertility and harvest. His role as a symbol of strength and procreation extended to the concept of kingship, and he was often associated with the pharaoh’s divine right to rule.

33. Khepri

Khepri was associated with the concept of rebirth and transformation. His name, pronounced as “Kep-ree,” means “He Who Is Coming into Being” or “The One Who Creates.” Khepri was typically depicted as a scarab beetle or a man with a scarab beetle head, underlining his connection to the insect.

The scarab beetle was a symbol of regeneration and transformation in ancient Egypt because of its habit of rolling balls of dung, a behavior that was likened to the sun pushing the solar disk across the sky. Khepri was seen as a representation of the sun god Ra at his dawn, facilitating the cycle of the sun’s rebirth each day.

Khepri’s mythology emphasized the idea of transformation and renewal. He was believed to roll the sun across the sky during the day and then guide it safely through the underworld during the night, ensuring its rebirth at dawn. This role in the solar cycle showcased the importance of continuity and rebirth in Egyptian cosmology.

Khepri was also invoked in the context of personal transformation and rebirth, reflecting the ancient Egyptians’ belief in the possibility of spiritual renewal and personal growth. His enduring significance in Egyptian culture emphasized the profound connection between the natural world, the cycle of the sun, and the potential for personal transformation and renewal.

34. Hapy

Hapy was closely associated with the annual flooding of the Nile River, a crucial natural event that brought fertility and sustenance to the land of Egypt. The name Hapy, sometimes spelled Hapi, is pronounced as “Hay-pee” and signifies abundance and prosperity, aligning with the river’s life-giving qualities.

Hapy was usually depicted as a man with a prominent belly, symbolizing fertility and plenty. His skin was blue or green, representing the water, and he often wore a headdress made of aquatic plants, like papyrus and lotus flowers. These plants were not only important for the ecosystem but also carried significant symbolism in Egyptian culture.

As the god of the Nile inundation, Hapy was venerated for his role in the agricultural cycle. The annual flooding of the Nile deposited nutrient-rich silt onto the fields, ensuring a bountiful harvest. Hapy’s blessings were integral to the prosperity of the Egyptian people and the kingdom’s well-being.

Hapy was sometimes depicted in a gender duality, with an effeminate and a masculine aspect, which represented the two sources of the Nile, the Blue Nile and the White Nile, respectively. His dual nature emphasized the importance of both rivers in the annual inundation.

35. Thoth

Thoth was the god of wisdom, writing, magic, and the moon. His name, pronounced as “Toth,” is often interpreted as “He Who is Like the Ibis” or “The Measurer.” Thoth was typically depicted as a man with the head of an ibis, a wading bird associated with the marshes along the Nile.

Thoth played a multifaceted role in Egyptian culture, serving as the scribe of the gods and the keeper of divine knowledge. He was credited with the invention of writing and was believed to have authored important texts, including the Book of the Dead, a guide to the afterlife.

As the god of wisdom and judgment, Thoth was associated with Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice. He played a vital role in the weighing of the heart ceremony, where he determined the righteousness of the deceased in the afterlife. This concept of judgment and balance was central to Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife.

Thoth was also a patron of magicians and healers, and he was invoked for his ability to decipher and manipulate the magical arts. He was often depicted carrying a staff and an ankh, symbolizing life and immortality.

36. Seshat

Seshat was revered as the deity of wisdom, knowledge, and writing. Her name, pronounced as “Seh-shat,” means “She Who Scratches” or “The Scribe,” emphasizing her role as a patron of record-keeping and scholarship. Seshat was often depicted as a woman wearing a panther-skin dress and a headdress resembling a seven-pointed star or a leafy crown.

Seshat was closely associated with the god Thoth, who was the deity of wisdom and writing. Together, they played essential roles in preserving and organizing knowledge, particularly in the context of temple rituals, ceremonies, and royal decrees.

Seshat’s primary function was to record the pharaoh’s deeds, especially the construction of temples and monuments, as well as the counting of the years of the king’s reign. She was believed to hold a palm stem with which she inscribed the names of pharaohs on the leaves of the sacred Ished tree, symbolizing the extension of their rule.

In addition to her role as a record-keeper, Seshat was associated with the measurement and layout of sacred architecture. She was invoked in the construction of temples and the establishment of cosmic order in Egyptian society.

37. Neith

Neith was revered as a deity of war, weaving, wisdom, and creation. Her name, pronounced as “Nayth” or “Neet,” is often translated as “Mistress of the Bow” or “The Great Cow,” emphasizing her dual roles as a powerful warrior and a nurturing mother figure.

Neith was typically depicted as a woman wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt or as a lioness, symbolizing her attributes of strength and ferocity. Her headdress often included crossed arrows, underscoring her association with archery and war.

As a goddess of war and protection, Neith was invoked for her power to defend and guard. She was seen as a protector of pharaohs and a guardian of temples and cities, including her cult center in Sais.

Neith’s importance extended to wisdom and creation. She was associated with the concept of creation through her role in weaving the fabric of the cosmos. The act of weaving was seen as a metaphor for the creation and sustenance of the world.

Neith was also linked to the primeval waters and was often associated with the goddess Hathor. In some myths, she was regarded as the mother of Ra, the sun god, emphasizing her role in the creation of the universe.

38. Khnum

Khnum was revered as the creator and the god of fertility, especially in relation to the annual flooding of the Nile River. His name, pronounced as “Kuh-num” or “Kuh-noom,” translates to “The Molder” or “The Fashioner,” emphasizing his role as a divine craftsman and shaper.

Khnum was typically depicted as a man with a ram’s head or as a ram. Rams were considered symbols of virility and fecundity, connecting Khnum to the generative forces of nature.

One of Khnum’s primary roles was to create human bodies and fashion them from clay on a potter’s wheel. This act was believed to take place in the Cavern of the Primeval Waters, representing the cosmic womb from which life emerged. Khnum was also associated with the annual inundation of the Nile, which brought nutrient-rich silt to the fields and ensured a bountiful harvest.

Khnum’s importance extended to concepts of rebirth and regeneration. He was believed to breathe life into human beings and to shape their destinies. He was often invoked in funerary rites to ensure the deceased’s journey to the afterlife and rebirth.

39. Satet

Satet was primarily associated with the Nile River, particularly its annual inundation. Her name, pronounced as “Sah-tet” or “Sat-it,” means “She Who Shoots” or “She Who Pours,” emphasizing her role in the flooding and fertility of the Nile.

Satet was typically depicted as a woman wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt or as a female deity with a headdress resembling an ankh symbol, often holding an ankh in one hand and a staff in the other.

As a goddess of the Nile, Satet was venerated for her ability to bring fertility and abundance to the land through the river’s annual flood. The Nile’s inundation was a critical event for ancient Egypt, as it deposited nutrient-rich silt, ensuring fertile soil for agriculture.

Satet was also associated with the concept of purification and renewal, often invoked to cleanse and bless the waters of the Nile. Her role as a purifier underlined the importance of maintaining the river’s purity for the well-being of the people and the prosperity of the kingdom.

In some mythological contexts, Satet was linked to the goddess Hathor, showcasing her multifaceted roles in Egyptian beliefs, including fertility, purification, and maternal attributes.

40. Wadjet

Wadjet was revered as the protector of Lower Egypt and a symbol of divine authority and power. Her name, pronounced as “Wadj-et” or “Uatchit,” means “Green One” or “The Green Goddess,” reflecting her association with the color green and the fertile vegetation along the Nile.

Wadjet was typically depicted as a cobra or a woman with the head of a cobra. The cobra was a potent symbol of protection and was often worn as an amulet by both royalty and commoners.

As the goddess of Lower Egypt, Wadjet was considered one of the two patron deities of the nation, along with Nekhbet, the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt. Together, they symbolized the unification of the two lands.

Wadjet’s image was often invoked in royal regalia and state symbols, including the uraeus, a stylized representation of a cobra, which was worn on the pharaoh’s crown to signify divine protection and authority. The uraeus was also a symbol of aggression against the enemies of Egypt.

41. Nekhbet

Nekhbet was revered as the protector of Upper Egypt and one of the patron deities of the nation, symbolizing maternal care and sovereignty. Her name, pronounced as “Nekh-bet,” means “She of Nekheb,” referring to her cult center in Upper Egypt.

Nekhbet was typically depicted as a vulture or a woman with the head of a vulture. The vulture was seen as a symbol of maternal protection, as it was believed to shelter its young beneath its wings. This imagery reinforced Nekhbet’s role as a guardian goddess and a protector of the pharaoh and the people of Upper Egypt.

As one of the Two Ladies, along with Wadjet, the cobra goddess of Lower Egypt, Nekhbet symbolized the unity of the two lands, Upper and Lower Egypt. She was often associated with the White Crown, the emblem of Upper Egypt, worn by the pharaoh.

Nekhbet’s significance extended beyond protection to sovereignty and legitimacy. She was believed to be the divine mother of the pharaoh, and her presence was invoked to ensure the rightful rule and authority of the king.

42. Serket

Serket was revered as a deity of protection, healing, and the afterlife. Her name, pronounced as “Serket” or “Selkis,” means “She Who Causes the Throat to Breathe” or “She Who Breathes,” underlining her role in safeguarding and healing the living and the deceased.

Serket was typically depicted as a woman with the head of a scorpion or as a woman with a scorpion perched on her head. Scorpions were both feared and respected in ancient Egypt due to their potentially lethal stings, and Serket was invoked to protect against their harm.

One of Serket’s significant roles was as a guardian of the canopic jars, which held the preserved organs of the deceased during the mummification process. She was associated with the protection of the deceased and their organs, ensuring a successful journey to the afterlife.

Serket was also linked to the concept of healing, particularly in the context of venomous stings and bites. She was believed to possess the power to counteract the effects of such poisons, making her an important figure in ancient Egyptian medicine and medical rituals.

43. Anuket

Anuket, an ancient Egyptian goddess, was venerated as the personification of the Nile River’s nourishing and life-giving qualities. Her name, pronounced as “An-oo-ket” or “Anqet,” means “The Embracer” or “She Who Embraces,” highlighting her association with the river’s fertile inundation.

Anuket was typically depicted as a woman wearing a headdress with tall plumes and holding a scepter in one hand and an ankh in the other, symbolizing life and stability. Often, she was depicted with a gazelle or antelope headgear, emphasizing her connection to wildlife and the river’s ecosystem.

As the goddess of the Nile, Anuket was venerated for her role in the annual flooding that brought nutrient-rich silt to the fields, ensuring abundant harvests. She was considered the life force of the river and a symbol of fertility.

Anuket’s cult centers were located in Upper Egypt, particularly in the area around Elephantine Island, where she was a prominent deity. Her worship often involved rituals and festivals dedicated to the Nile’s inundation and its vital role in the prosperity of the land.

Conclusion

The Egyptian pantheon is a rich tapestry of deities, each with its unique attributes, roles, and symbolism. While they don’t have a conventional family tree in the way humans do, the gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt are often interconnected through mythology, cosmology, and their roles in Egyptian culture.

While these gods and goddesses do not form a family tree in the traditional sense, their interwoven roles and mythologies collectively shaped the complex and enduring belief system of ancient Egypt, which emphasized the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, as well as the importance of balance, order, and the natural world in the lives of the Egyptian people.

Comments